Tags

It’s all too unfortunate how much we can learn about someone once they’ve passed away. All secrets can come to light after we’ve died. If our death is through an unfortunate accident, a coroner can perform an autopsy and find out what we’ve been eating, snorting, ingesting, imbibing, what Rxs we’ve been taking, what diseases we may or may not have. They could do a genetic profile, and if we’ve giving consent, use our organs as a gift of life or to teach medicine to others. Beyond that, our words, our deeds, our dreams and our shortcomings are all there for others to look at. All anyone has to do is be curious.

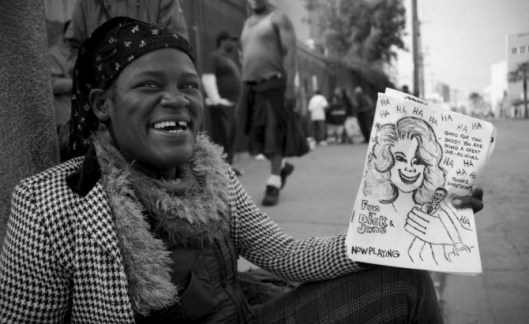

That’s been the case so far as I’ve looked into the life of the late Brandie Weston off and on over the past twenty-one months. In that time, I haven’t learned much more than what I already knew about her last years before her death in August ’07. Through public records, I discovered that Brandie had left New York sometime in ’02, lived for a while in Montana, spent a bit of time in the Bay Area, and made her way to L.A. and Santa Monica by ’05 or ’06. She had been homeless pretty much that whole time. There’s also evidence of vagrancy arrests and her own paranoia regarding the police and being medicated through the bits and pieces I and one of her best friends from our high school days pulled off of the Internet.

I’d like to know more about Brandie’s last years and days, but that’s going to take a lot more work, like an investigative story piece. I need to reach out to her mother again, who didn’t want to talk about what happened when I called her a year ago. I might have to contact her sister, but that may mean opening up some bad memories for both of us. It may even mean me going to Santa Monica or L.A. to talk to folks at local homeless shelters. That, of course, takes money, and I’m pretty tapped out right now from doing Boy At The Window in terms of tracking down people and memories.

But I’ve learned a bit more about how Brandie lived in her years after high school. I’ve received at least a dozen emails from her SUNY Purchase classmates and friends, and some anonymous communications as well. All of them seemed shocked about Brandie’s end. All of them seemed like they knew Brandie — or at least a side of her — better than anyone she grew up around. All of them seemed like they would’ve wanted as much information about her mental illness and homeless state as they could’ve gotten in real time during all of those years before her death. It was nice to know that Brandie’s calling as a music artist took her to places that she did want to go, and that her SUNY Purchase and other friends wanted to go there with her.

This is as important a lesson as anyone can learn from life. However we leave this world, it’s important to have touched as many lives as possible with your calling, your dreams, your successes, even your shortcomings. It’s always important to have friends in your life who know the real you, not the one you have to show at work to get a promotion or at home to please family or at school to satisfy your teachers and your alleged friends. From the looks of things, Brandie had more than a few of those.

But not in total. Obviously Brandie didn’t exactly go around sharing the news of her mental illness and her homelessness with most folks. From what I’ve uncovered so far, she also didn’t share too much about her family or her Mount Vernon, New York past either. That’s unfortunate, and for several reasons. These college and music artist friends were the people most likely to have understood what she was going through and how much hell she had to go through in her final years. They would’ve been there for her in ways that even her family couldn’t (and likely wouldn’t) have been. Keeping her past, her struggles, her emotional aches and pains, the things that vexed her all bottled up couldn’t have helped her state of mind or decision-making in the years after ’02. It would’ve tormented Brandie, as it would anyone with aspirations and the talent to reach them under less trying circumstances.

As a writer and an educator, I understand the grand irony of a calling. That without the pain and trauma of the past, I wouldn’t be the writer or the teacher that I am today. For Brandie, those things should’ve driven her, maybe even made her a better singer and artist. There’s a danger to embracing one’s past and one’s pain, though, because both can become an addiction, driving people out of one’s life in the process. In the case of a couple of our former high school classmates, I think that’s exactly what happened. I just wish that Brandie had at least given her SUNY Purchase friends a chance to know that part of her before she died, and certainly before she left on a multi-year, homeless, cross-country journey to nowhere.

It makes me think of the still relatively new Nickelback song, “If Today Was Your Last Day.” What would really matter? Who would I choose to spend my last twenty-four hours with? As much as I want to publish Boy At The Window, I’d likely spend the day with everyone I’ve ever loved, make amends to whomever I felt I needed to, and go to a park to spend time enjoying nature. I’d leave my book manuscript with someone whom I could trust to publish it. I’d make them promise, but then I wouldn’t think about it again. I hope that Brandie didn’t spend so much of her precious few moments of clarity thinking about what could’ve been. I hope that those of us still here do make the most of Brandie’s warning to us to get our acts together while we still can.